General elections were held in South Africa on 29 May 2024 with a voter turnout of 58.6% (vs. 66% in 2019), the lowest on record since universal suffrage was implemented in 1994. The final results were declared three days later, on 2 June. Parliament (composed of the National Assembly and the National Council) has 14 days after the announcement of the results to elect a President. These results were highly anticipated, as, for the first time in the post-apartheid era, the African National Congress (ANC) was widely expected to lose its absolute majority, which it ultimately did. These results put the ANC and President Cyril Ramaphosa in a tight spot regarding the formation of a governing coalition, as the results of its smaller partners are insufficient to secure a 50 + 1 majority (or 204 MPs in the 400-seat National Assembly), raising uncertainty for the coming years.

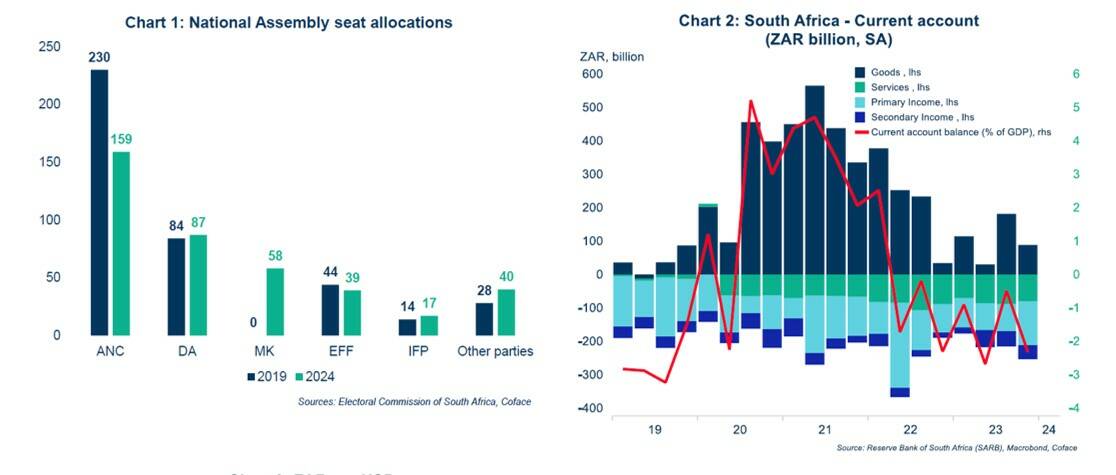

The ANC’s result was even worse than expectations, as it barely secured 40% of the vote for the National Assembly (159 seats) vs. 57.5% in the 2019 elections (230 seats). The centrist Democratic Alliance (DA), the main opposition party, came in second with 21.8% (87 seats) of the vote. The biggest surprise was the strong showing of uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK party), launched in December 2023 by ex-president Jacob Zuma (in office from 2009 to 2018, but ineligible at this election due to a criminal conviction), which secured 14.4% of the vote (58 seats). Meanwhile, the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), the traditional third political force in the country since 2014 and led by Julius Malema, came in fourth at 9.7% (39 seats) (Chart 1).

Regarding the 9 Provincial Parliaments, the ANC’s results were also very poor. It maintained an absolute majority in only 5 provinces (vs. 8 in 2019), barely missing it in Northern Cape (49.3% vs. 57.5%) and keeping a very slim majority in Gauteng (34.8% vs. 50.2%). The DA kept its hold on Western Cape (55.3%), but more critically, the ANC outright lost the majority in Kwazulu-Natal, the second-most populous province, where MK came in first at 45.4%, followed by the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) at 18%.

This general election marks a historic reconfiguration in South African politics. The fact that the ANC, the party of Nelson Mandela that carries the legacy of ending the apartheid, is challenged to this extent signals that its aura (and historic voter base) is no longer sufficient to overcome South Africans’ long-standing perception of poor governance, looting of state assets, numerous corruption scandals and long-lasting social issues (unemployment, inequality, crime, etc.). Furthermore, the progress made on the back of Black Empowerment policies has not benefited the black population in an even manner, and the white population has conserved its position, especially in the economy. Not only do these results mean that the ANC will no longer be able to govern alone, but it also signals a potential shift in the party’s configuration, as the choice of the coalition partners is also likely to change the balance of power between the ANC’s internal factions.

Risks

Uncertainty regarding the governing coalition

Currently, there is still no clear-cut answer on the form of a future coalition. The ANC’s National Executive Committee, the party’s primary decision-making body, is currently discussing its options. President Ramaphosa will have to be reinstated before the end of the 14-day period by the Parliament, as he is expected to remain the leader of the majority party. The question is will he obtain a governing coalition with an absolute majority or will he have to contend with a simple majority. It appears unlikely that the ANC would consider an alliance with the MK party, as it would mean giving significant political leverage to Jacob Zuma who has previously indicated that he would only support such a move if President Ramaphosa were removed from office. This would be viewed as a significant regression for the ANC. As such, two main scenarios are being considered at this stage, both of which are likely to cause internal friction within the party:

- The ANC decides to form a unity government with the DA and the IFP (notably due to its results in Kwazulu-Natal). Considering the DA’s more liberal stance on the economy, this would resonate with Cyril Ramaphosa’s commitment to solving issues crippling the economy. This most notably includes reforms to increase the role of the private sector in the economy to address the crises that Eskom (the national power utility) and Transnet (the national rail, port, and pipeline operator) are facing. An alliance between the ANC and the DA would also be a positive signal for international investors. However, this would be met by strong opposition within the ANC, especially from its more radical factions, which still perceives the DA as a party representing wealthy pro-market whites. This perception clashes with core values of these factions, including Black Empowerment, and a strong role of the state in the economy.

- The ANC decides to form an alliance with the EFF and other smaller partners, which would secure enough MPs to form a governing majority. Some ANC heavyweights, such as the former energy minister Gwede Mantashe, favour this solution. Moreover, and maybe more importantly, some surveys also show that ANC voters would be more inclined towards an alliance with the EFF than with the DA. Currently, the EFF’s condition for an alliance is to obtain the finance ministry and the speaker of the National Assembly. The EFF’s economic stance is much more radical, with further nationalisation (for instance in the mining industry and the banking sector) and land expropriation of white-owned farmland. This outcome would weaken Ramaphosa as the radical faction of the ANC would gain considerable weight in decision-making, and most probably hamper his ability to push through his reform agenda. Markets would also react more negatively to this outcome.

Social tensions

While the elections were held peacefully, and the Electoral Commission confirmed the results, Jacob Zuma has requested a recount of the vote due to what he considers “irregularities”. More concerning, he has also stated that there could be “trouble” if his demand was not met. Considering the extremely violent riots that broke out in July 2021 following his imprisonment, and the strong support for the MK party in Kwazulu-Natal, there is still a risk that social tensions rise in the aftermath of the elections.

Hampering the reform agenda

South Africa’s economy has been struggling for over 15 years, a period characterized by low growth, extremely high unemployment (33% overall, 45.5% for the youth), poor maintenance of critical infrastructure and lacklustre governance of large SOEs. This was exacerbated in recent years both by the impacts of global shocks such as the pandemic and the Ukraine war, and significant domestic crises that culminated in the failure of the country’s energy, water, and logistics systems. As a coalition government is new to South Africa and innately more unstable, there are now concerns regarding the future of stable governance, at a time when the country needs implementation and continuity of critical reforms to restore economic stability.

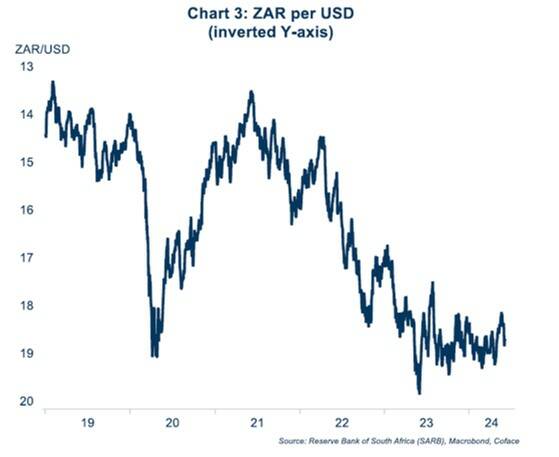

Fluctuations in investor confidence

The South African economy is particularly vulnerable to shifts in investor confidence. After two years in surplus, South Africa’s current account reverted to a deficit in 2022 (Chart 2) that is expected to widen in the next years (-2.6% of GDP forecasted for 2024), mainly due to lower prices for the export commodity basket combined with higher import prices, as well as large profit repatriations of foreign companies. This means that financing needs will increase. While FDI have been quite solid in recent years, the South African economy remains very sensitive to volatile capital flows due to its large equity and bond markets. Capital outflows triggered by a deterioration of investor confidence due to the outcome of the election would add to the already increasing financing needs, and further pressure the rand, which has weakened against a still strong USD (Chart 3). The weakness of the rand has implications on imported inflation, which partly explains why despite ongoing disinflation, the inflation rate in South Africa remains sticky (5.1% as of April 2024) and is expected to return to the SARB’s target (midpoint of the 3-6% range, i.e. 4.5%) only by end-2025. This in turn implies restrictive monetary policy for longer (repo rate maintained at 8.25% since May 2023, from 4% in February 2022), pressuring already low growth.